Issue

Critical and strategic minerals are essential to the economic and national security of both industrialized nations like the United States and developing countries. They are key to manufacturing and agricultural supply chains, and to the successful deployment of modern technologies in a variety of industries, including telecommunications, national defense, and both conventional and renewable energy.

Background

Minerals are deemed “critical and strategic” because they are essential to the economic and national security of the United States and because the U.S. is dependent on imports, not only from China and Russia, but also from other nations (1), for most if not all of our domestic supply.

The U.S. has vast mineral resources, but is becoming increasingly dependent upon foreign sources for these critical mineral materials, as demonstrated by the following:

-

The U.S. is import reliant on minerals from dozens of nations, some of which are located in politically unstable regions of the world, often governed by regimes whose interests are not aligned with those of the U.S. Other countries engage in unfair business practices, including predatory pricing, to control markets and manipulate global supply.

-

In 1995, the U.S. was dependent on foreign sources for 47 nonfuel mineral materials, 8 of which the U.S. imported 100 percent of the Nation’s requirements, and for another 16 commodities the U.S. imported more than 50 percent of the Nation’s needs. [2]

-

By 2017 the U.S. import dependence for nonfuel mineral materials increased from 47 to 53 commodities, 21 of which the U.S. imported for 100 percent of the Nation’s requirements, and an additional 32 of which the U.S. imported for more than 50 percent of the Nation’s needs. [3]

-

In May 2018, the Department of the Interior published a list of 35 critical minerals (See, “Final List of Critical Minerals 2018” 83 Fed. Reg. 23295; 2018 https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/05/18/2018-10667/final-list-of-critical-minerals-2018). The U.S. is import reliant (imports are greater than 50% of annual consumption) on 31 of those 35 minerals and relies 100% on imports of 14 of those minerals.

-

The assured supply of critical minerals and the threats to their supply chains are so great that President Donald J. Trump issued Executive Order 13817, A Federal Strategy to Ensure Secure and Reliable Supplies of Critical Minerals. That Order directed the Secretary of Commerce, in cooperation with the heads of selected executive branch agencies and offices to submit a report to address these challenges.

-

The Department of Commerce, working in concert with other executive branch agencies, completed that report in June, 2019. That report presents 6 Calls to Action, 24 goals, and 61 recommendations that describe specific steps that the Federal Government will take to achieve the objectives outlined in Executive Order 13817.1

-

President Trump subsequently issued Executive Order 13953 declaring a national emergency to expand domestic mining of such minerals, in part through the use of the Defense Production Act. Citing the U. S. dependence on China for 80% of critical minerals needs and vulnerability in critical supply chains, the President also ordered federal agencies to reduce unnecessary delays in permitting actions. The recent action is designed to more swiftly implement the prior 2017 Executive Order on critical minerals. See, 85 FR 62539 (October 5, 2020).

-

The new Administration under President Joe Biden continues to recognize the need for secure, domestic mineral supply chains. Biden has left the prior Executive Orders in place and further issued EO 14017 on February 24, 2021. See, 86 FR 11849 (March 1, 2021). That order directs the Secretary of Defense to submit a report identifying risks in the supply chain for critical minerals and other identified strategic materials, including rare earth elements, and policy recommendations to address these risks.

-

According to the United States Geological Survey’s 26th Annual Mineral Commodity Summaries report issued February 2, U. S. dependence on imported minerals continues to grow. Imports made up more than one-half of U.S. consumption for 46 nonfuel mineral commodities and the United States relied entirely on imports for 17 of those. Of those 17, 14 are identified as critical minerals. Another 14 critical minerals had a net import reliance greater than 50 percent, most of which were supplied to the U. S. by China. See, Mineral Commodity Summaries 2021 at 5-6; https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2021/mcs2021.pdf

Definition - Critical Materials

As defined by Presidential Executive Order No. 13817, “a critical mineral is a mineral (1) identified to be a nonfuel mineral or mineral material essential to the economic and national security of the United States, (2) from a supply chain that is vulnerable to disruption, and (3) that serves an essential function in the manufacturing of a product, the absence of which would have substantial consequences for the U.S. economy or national security”.

Uses [4]

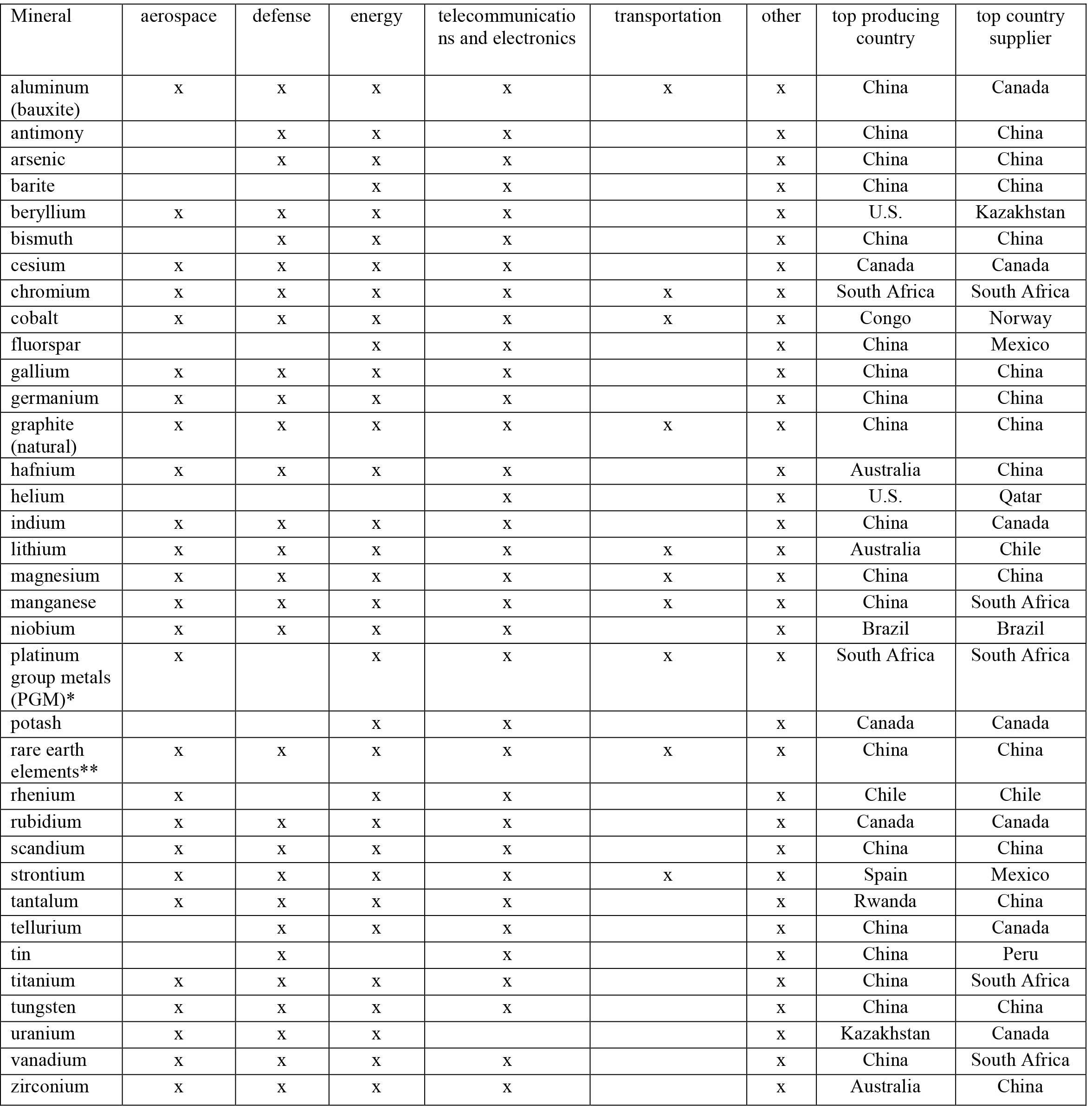

Critical and Strategic minerals are part of virtually every product we use (Table 1).

Energy Technologies: Indium, gallium, germanium, selenium, tellurium, neodymium, lanthanum, tantalum, vanadium, lithium, silicon, platinum, cobalt, nickel, arsenic and silver are key minerals for producing solar photovoltaic, thermal solar, wind power, electric and hybrid vehicles.

Aerospace, Communications and Defense: These key industries rely upon a supply of vanadium, rhenium, cobalt, nickel, niobium, neodymium, samarium, cobalt, yttrium, terbium, europium and erbium used in fighter jets, drones, tanks, radios, shielding, and other combat equipment.

Battery technologies: Require cobalt, graphite, lithium, and manganese.

Electronics/Lighting: Require praseodymium, samarium, scandium, europium, gallium, indium, germanium, tin, cerium, lanthanum, zinc and selenium.

TABLE 1. Critical minerals in the U.S. and their primary industry use [2, 3]. *Platinum group metals include ruthenium, rhodium, palladium, osmium, iridium, and platinum. **Rare earth elements include the 15 lanthanide elements (lanthanum, cerium, praseodymium, neodymium, promethium, samarium, europium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, holmium, erbium, thulium, ytterbium, and lutetium) and many times yttrium and scandium are included as rare earth elements. [click to expand]

Restrictions on the supply of any given mineral would significantly impact consumers and key sectors of the U.S. economy. Risks to minerals supplies could include a sudden increase in demand, difficulty in extracting the mineral or even exhaustion of the resource itself. Delay alone in issuing permits is a significant impediment to the production of critical minerals. For example, mining permits currently take 10 to 15 years to obtain, primarily due to duplicative and overlapping federal agency requirements and agency reviews. Minerals are more vulnerable to supply restrictions if they come from a limited number of mines, mining companies or nations. This is especially true in the case of critical and strategic minerals. Baseline information on minerals is currently collected at the federal level, but no established methodology currently exists to identify potentially critical and strategic minerals.

Issue

Lack of secure supply chains for some minerals critical to clean energy technologies hinders U.S. manufacturing and energy security. These critical materials (a) provide essential and specialized properties to advanced engineered products or systems for which there are no easy substitutes and (b) are subject to supply risk. Rare Earth Elements, with essential roles in high-efficiency motors and advanced lighting, are the most prominent of the critical materials today [8].

The economic importance of critical and strategic minerals, increasing global competition for them by rapidly developing countries, and the potential for supply disruptions triggered a study by the National Research Council (NRC), “Minerals, Critical Minerals, and the U.S. Economy.” [5] This report included the criticality evaluation matrix (Figure 1) that relates the importance and availability of a mineral. The matrix uses evaluations of the impacts of supply restrictions (the importance of the mineral) to the potential for supply disruptions. The greater both of these measures the more critical the mineral. [6]

A mineral commodity’s importance can be characterized by factors such as the dollar value of its U.S. consumption, the ease with which other minerals can be substituted for it, and the outlook for emerging uses that can increase its demand. A way to evaluate the significance of these factors is to consider the impact that a lack of availability would have on them. How would the mineral’s uses or price change if it were less available? A mineral’s availability depends on several factors including how much has been discovered, how efficiently it can be produced, how environmentally and socially acceptable its production is, and how governments influence its production and trade. Many of the technological, social and political factors have become increasingly important influences on mineral availability. For example, China produces most of the world’s Rare Earth Elements. By curtailing export shipments of these technologically key elements in 2010, China drastically affected their global availability. [6]

The Exclusion of Uranium from the Published List of Critical Minerals Increases U.S. Dependence on Imports, Jeopardizing National Security

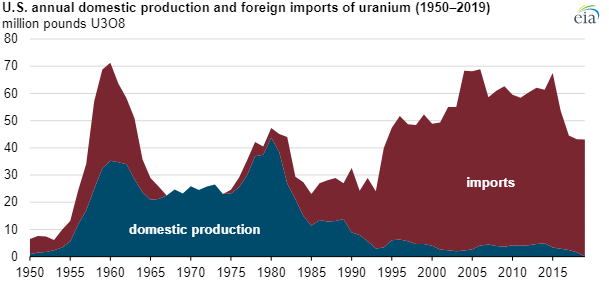

Although the U.S. was a world leader in the production of uranium until 1980, nearly all of the uranium used in the generation of electricity from nuclear generating facilities and in the manufacture of other products comes from foreign sources. The graph below illustrates the decline in U.S. production, which hit a low in 2019, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA).

Today, the U.S. imports 90% of the uranium used to meet domestic power and other needs. https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=40134. Only 33% of the uranium used here in the U.S. is imported from Canada and Australia. More than 51% is imported from other nations, including Russia (16%), Kazakhstan (22%), Uzbekistan (8%), and Namibia (5%).i In contrast to the U.S., where permitting delays hinder the development of new mining projects, uranium producers in many foreign countries are state owned enterprises that are heavily subsidized and supported by their governments, so much so that such enterprises dominate the list of top worldwide uranium producers.ii

Notwithstanding the importance of uranium’s use in meeting critical defense needs and in the transition to a clean energy economy (nuclear power produces zero emissions), the U.S. Geological Survey removed uranium from the most recently published draft list of critical minerals. 86 Fed. Reg. 62199, 62200 (November 9, 2021). The stated basis for this action was that the Energy Policy Act of 2020 excludes mineral fuels from the definition of critical minerals and that uranium is defined as a mineral fuel under the Mineral Policy Act of 1970. The USGS’ announcement, however, does not discuss the important non-fuel uses of uranium in munitions armor, radiation shielding, and aircraft parts, as set forth in a U.S. Department of Commerce Report on the effects of imports of uranium on national security. 86 Fed. Reg. 41540, 41565 (August 2, 2021).

SME Statement of Technical Position

- SME supports a streamlined U.S. permitting process for critical and strategic minerals and the study of options to remove impediments to the timely issuance of such permits. The elimination of duplicative federal agency oversight, i.e. “one stop shopping” would speed the responsible development of these resources.

- SME generally endorses the Commerce Department initiative and effort, and pledges to work constructively to assist in helping the private sector and government attain the goals outlined therein, i.e. the reduction of U.S. reliance on imports of critical and strategic minerals through increased production here in the United States.

- The Department of the Interior should revise the methodology currently used to identify potential critical minerals [7, 9] as more information is obtained.

- The U.S. through the U.S Geological Survey and state geological surveys should continuously conduct, revise and update a comprehensive inventory of critical and strategic mineral resources. Geologic, geophysical, geochemical, and other basic data should be obtained to properly evaluate critical minerals in the United States.

- The U.S. should develop criteria to govern the addition or removal of minerals or materials from the critical minerals list.

- The U.S. Geological Survey should reconsider its decision to remove uranium from the list of critical minerals, given the important non-fuel uses of uranium in the manufacture of products essential to U.S. national defense and security.

- Industry, academia and government should explore and implement partnerships to address demographic and other challenges that impact U.S. mineral production, including the aging and declining workforce, as well as the decrease in mining, mineral engineering and economic geology programs at colleges and universities The enhancement of these educational programs will help grow the critical minerals workforce.

- SME further supports the development of effective outreach efforts to the general public to convey the importance of critical minerals to the U.S. economy and national security.

References

[1] U.S. Geological Survey, 2019, Mineral commodity summaries 2019: U.S. Geological Survey, 200 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/70202434.

[2] United States Geological Survey, 1996, “Mineral Commodity Summaries 1996,” USGS, Reston, VA.

[3] United States Geological Survey, 2018, “Mineral Commodity Summaries 2018,” USGS, Reston, VA, 204 p.

[4] Colorado Geological Survey, “Critical and Strategic Minerals of Colorado,” www.coloradogeologicalsurvey.org.

[5] American Geosciences Institute, 2010, “Critical Minerals,” Earth Notes, AGI, Alexandria, VA, 1 p.

[6] National Research Council, 2008, “Minerals, Critical Minerals, and the U.S. Economy,” National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 245 p.

[7] Schulz, K.J., DeYoung, J.H., Jr., Seal, R.R., II, and Bradley, D.C., eds., 2017, Critical mineral resources of the United States—Economic and environmental geology and prospects for future supply: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1802, 797 p., http://doi.org/10.3133/pp1802.

[8] Verplanck, P.L. and Hitzman, M.H., 2016, Rare earth and critical elements in ore deposits: Society of Economic Geologists, Reviews in Economic Geology, v. 18

[9] Fortier, S.M., Nassar, N.T., Lederer, G.W., Brainard, Jamie, Gambogi, Joseph, and McCullough, E.A., 2018, Draft critical mineral list—Summary of methodology and background information—U.S. Geological Survey technical input document in response to Secretarial Order No. 3359: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2018–1021, 15 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr20181021.

i https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/nuclear/where-our-uranium-comes-from.php